What if you stood in a grand concert hall and heard two symphonies playing at once? One is familiar, a powerful Roman march full of order and imperial grandeur. But beneath it, you feel a deeper vibration—a bass note so profound and ancient it seems to come from the bedrock of the Earth itself. It’s a composition of impossible scale, one that stops abruptly mid-crescendo, leaving a silence that echoes louder than any music. This is the feeling of standing at Baalbek in Lebanon. It’s a place that presents us not with one story, but with the haunting fragments of two—and evidence of a masterpiece left tragically unfinished.

“For generations, we have been taught to hear only the Roman music. And what a magnificent piece it is.”

The Roman Overture We All Know: What Did the Romans Build at Baalbek?

To walk through the ruins of Heliopolis, the Roman “City of the Sun,” is to witness the sheer ambition of one of history’s greatest empires. The Temple of Jupiter, even in its shattered state, is a breathtaking monument. Six of its original fifty-four Corinthian columns still stand, soaring nearly 65 feet into the sky, a testament to the skill and organizational might of Roman builders.

We see their handiwork everywhere. The grand courtyards, the intricate carvings, the sheer scale of the complex—it all sings a song of Roman power. Their engineering prowess is legendary; they gave us aqueducts that carried water for miles and roads that bound an empire together. Here in Baalbek, we see their signature style. We see how they constructed their enormous columns in sections, or “drums,” stacking them one by one to achieve their towering height.

“This was the known and practiced method of the masters of the Mediterranean world.”

This is the symphony we came to hear. It’s the one written in our history books. But I invite you to lower your gaze. Look past the Roman overture and listen for the music it was built upon.

The towering Roman columns of the Temple of Jupiter at Baalbek, Lebanon, silhouetted against the setting sun.

The Silent First Movement: The Impossible Scale of the Baalbek Trilithon

Beneath the platform of the great Temple of Jupiter lies something else entirely. It’s a foundation so different in scale, material, and spirit that it feels alien to the Roman structure above it. This is the first, silent movement of Baalbek’s deep symphony: the legendary Baalbek Trilithon.

The Trilithon consists of three colossal blocks of limestone, set into the western retaining wall of the podium. To say they are large is a profound understatement.

“Each stone is over 60 feet long, 14 feet high, and 11 feet thick. Their estimated weight is a staggering 800 to 1,000 tons apiece.”

They are among the largest single building blocks ever moved in human history, fitted together with a precision that defies explanation.

To stand before them is to feel humbled. The Roman work above, for all its glory, feels almost temporary when compared to the eternal, elemental power of these stones. There are no sectional drums here. This is not construction; it is a statement. It is a bass note held for an eternity, a foundation built not for a temple of men, but for a landing place of gods.

This immediately presents us with a profound dissonance. If the Romans, with their known methods and tools, built this entire complex, why is the foundation so radically, impossibly different from everything else they ever built? Why compose a delicate melody on top of a thunderous, cyclopean chord? The truth may be that they didn’t write the first movement at all. They simply found the stage already built.

The three enormous megalithic stones of the Baalbek Trilithon, forming the foundation of the Temple of Jupiter. Image by Lodo27 from Wikimedia Commons under license CC BY-SA 2.0

The Unplayed Notes: The Unfinished Megaliths of the Baalbek Quarry

The story deepens when we leave the temple complex and journey about a quarter of a mile away, to the ancient limestone quarry. It is here that the mystery of Baalbek is laid bare, for here lie the unplayed notes of this interrupted symphony.

First, we encounter the famed “Stone of the Pregnant Woman” or Stone of the South (Hajjar al-Hibla). It is a monstrous, rectangular block, fully quarried on three sides, measuring nearly 70 feet long and weighing an estimated 1,200 tons. It lies there still attached to the bedrock, as if the workers who were shaping it simply put down their tools one afternoon and never returned.

“It was clearly destined for the temple platform, a fourth and even grander addition to the Trilithon.”

But it is not alone. Deeper in the same quarry, another, even larger stone was discovered in 2014. This behemoth weighs an unthinkable 1,650 tons. Like its sibling, it is perfectly hewn and shaped, awaiting a journey it would never take.

These stones prove, beyond any doubt, that the original construction of the megalithic platform was a project that was violently and suddenly halted. No builder in their right mind quarries and shapes their largest, most important pieces only to abandon them at the last moment. What could possibly stop a work of such magnitude? What could silence a project that was already achieving the impossible?

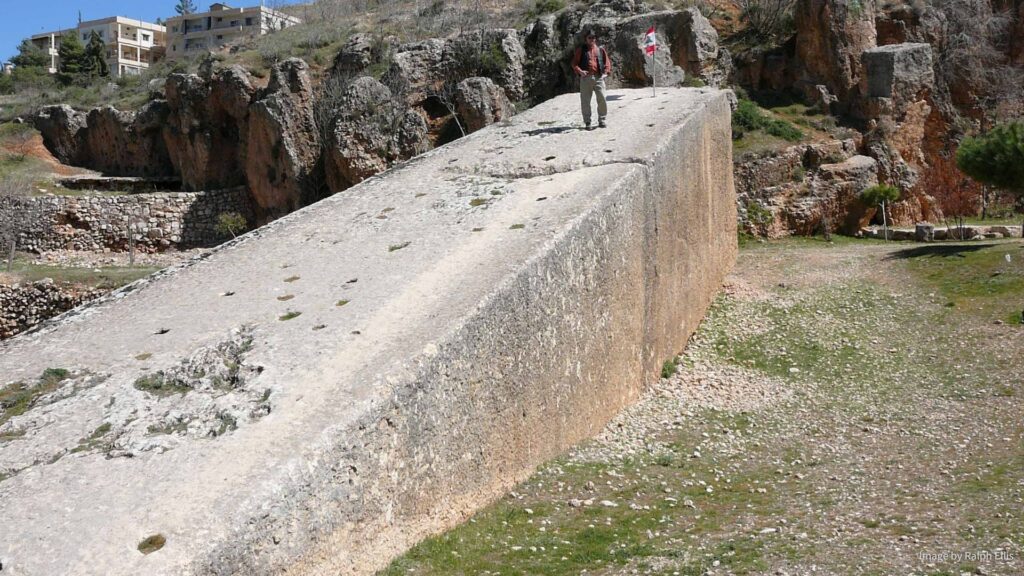

The massive, unfinished megalithic block known as the Stone of the South, still lying in the ancient quarry at Baalbek. Image by Ralph Ellis on Wikimedia Commons under license CC BY-SA 4.0

A Composition Beyond Roman Instruments: Could Roman Engineering Move the Trilithon Stones?

This brings us to a critical question of technology. Could the Romans have moved these stones? The historical and archaeological records are quite clear on this: absolutely not. The Romans were brilliant engineers, but their technology had well-understood limits.

The most powerful crane in the Roman arsenal was the polyspastos, a machine powered by large treadwheels and human laborers. Historical reconstructions and ancient accounts tell us that the maximum lifting capacity of the largest Roman cranes was somewhere between 50 and 60 tons. This was more than sufficient for their needs—lifting the drums of their columns, placing statues, and building their impressive architecture across the empire.

But the Trilithon stones are not 60 tons. They are over fifteen times that limit. The stones left in the quarry are more than twenty-five times that limit. There is simply no known Roman technology, no combination of levers, rollers, or manpower, that can account for the quarrying, transportation, and precise placement of stones of this magnitude.

“To suggest they did is to ignore the fundamental principles of physics and the extensive records of Roman engineering limitations.”

This is perhaps the most compelling evidence for a Pre-Roman Baalbek. The Romans did not build the megalithic foundation. They were like a later composer finding an unfinished masterpiece from a long-lost genius. Awed by its power, they did the only thing they could: they built their own, smaller symphony on top of it, leaving the giant, silent notes in the quarry untouched because their instruments were simply not capable of playing them.

Who Was the Original Composer? A Lost Civilization from the Younger Dryas?

If the Romans were not the original builders, then who was? This is where we step beyond the comfortable confines of mainstream history and into a deeper, more profound mystery. Who on this Earth possessed the lost ancient technology to accomplish such a feat?

When we look at Baalbek’s foundation, we must see it not as an isolated anomaly, but as part of a global phenomenon of ancient megalithic structures. From the impossibly cut stones of Puma Punku in the Andes to the deeply buried pillars of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, our planet is dotted with the remnants of a powerful, technologically capable, and globally connected culture that our history books have forgotten. They were the original composers of this planet-wide symphony in stone.

“So what could have interrupted them? What force could be so powerful as to halt construction at Baalbek and seemingly erase this entire civilization from the memory of mankind?”

A regional war or a dynasty’s collapse seems far too small an event. The evidence points to something far more terrifying: a global cataclysm.

Many researchers now point to the end of the last Ice Age, around 12,800 years ago, a period known as the Younger Dryas cataclysm. This was a time of unimaginable environmental upheaval—of comet impacts, global floods, and sudden, dramatic climate change. A catastrophe of this scale is perhaps the only event that could account for the sudden, violent end to Baalbek’s first movement. It wasn’t just a project that was halted; it was a world that was broken. The original symphony was silenced by the roar of a dying age.

Hearing the Echoes Today

Standing at Baalbek is an exercise in listening. It’s about learning to hear the deep, resonant hum of the Trilithon beneath the more familiar strains of the Roman ruins. It’s about understanding that we are looking at two different ages, two different humanities, and a story of a masterpiece that was never finished.

We are living in the long silence that followed that symphony’s abrupt end. The stones in the quarry are not just relics; they are a message. They speak of a capacity and an ambition within the human story that we have yet to reclaim. They challenge us to ask what we have forgotten and to wonder what else we might be capable of. The original composers are long gone, but their music, frozen in stone, is still waiting for us to finally learn how to hear it.

Join The Project

The inquiry doesn't end with this article. Our weekly newsletter is where The Project continues. Each week, we deliver new findings—from deconstructing ancient history to forging philosophical thought experiments. It's our expedition into the source code of the human story, delivered directly to your inbox.

We are JD Lemky. He’s a physical chemist trained in academic rigor; she’s an editor with degrees in both literature and biochemistry. We use a scientist’s skepticism and a storyteller’s eye to challenge the official history, exploring the echoes of lost worlds to find what they can teach us about our own.