Is there a more painful paradox in the human story? We build monuments to discovery and claim to worship the truth, yet our history is littered with the quiet tragedies of the truth-tellers themselves. It is an ancient, repeating pattern: an individual of immense courage and vision ventures beyond the comfortable map of their time—be it a map of the world, of science, or of philosophy. They return with a discovery so profound it promises to expand reality for everyone, only to be met with scorn, ridicule, and the volcanic fury of an establishment protecting its cherished dogmas.

“They bring back a bigger world, and in return, the world they sought to enlighten brands them a heretic, a madman, or a liar.”

To understand this timeless struggle, we must journey back over two millennia to the sun-drenched port of Massalia, the Greek colony we now call Marseille. Here lived a man named Pytheas, not just a sailor, but a brilliant astronomer and mathematician. In the 4th century BC, he embarked on a voyage that was not merely a geographical exploration, but a collision course with the perfect, settled science of his age. He sailed north, off the edge of all known maps, and into a world the greatest minds of his time, including Aristotle, had declared impossible.

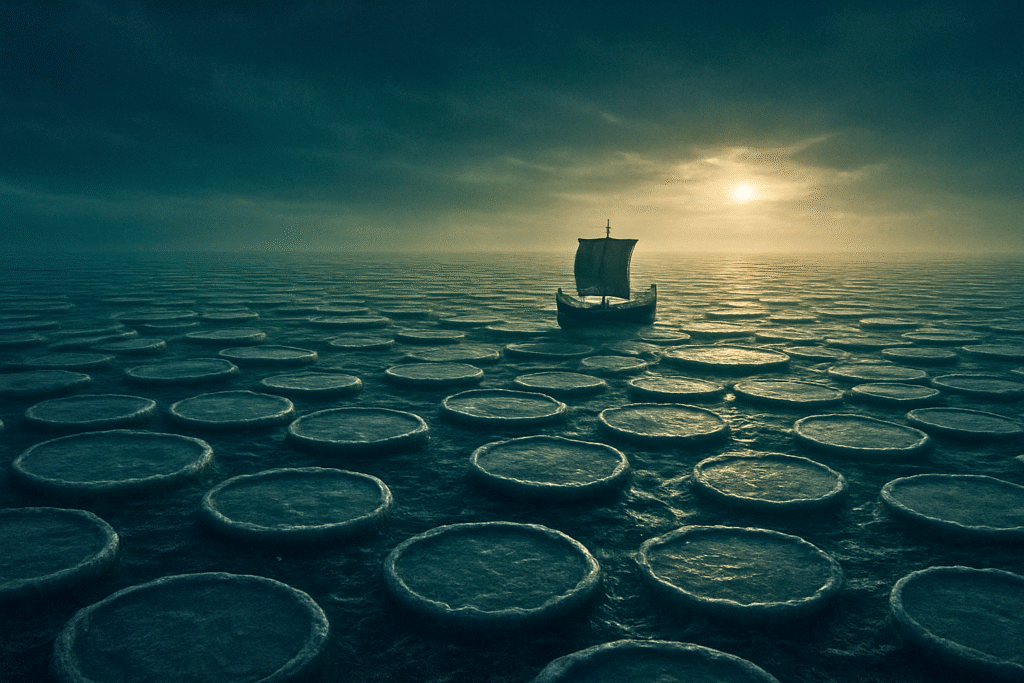

Picture him now, standing on the bow of his small wooden ship, the timbers groaning a language of protest against a sea as black as liquid night. The air is a thief, stealing warmth with a bite that feels solid, filled with microscopic shards of ice. And there, on the horizon of a world lit by a sun that refuses to set, he sees it. It is not land. It is not sea. It is something else entirely, a new state of being. The water ahead of him is covered in a moving, breathing skin of shifting ice plates. It rises and falls with the swell, a monstrous, gelatinous lung inhaling and exhaling at the edge of the world.

What he brought back from this voyage was more than a story; it was a truth that threatened the very foundations of Greek cosmology. His journey to the legendary land he called Ultima Thule was not just a battle against the elements, but a collision with the very limits of human understanding, and a perfect testament to the agony of seeing too far, too soon.

A Crack in the Crystal Sky

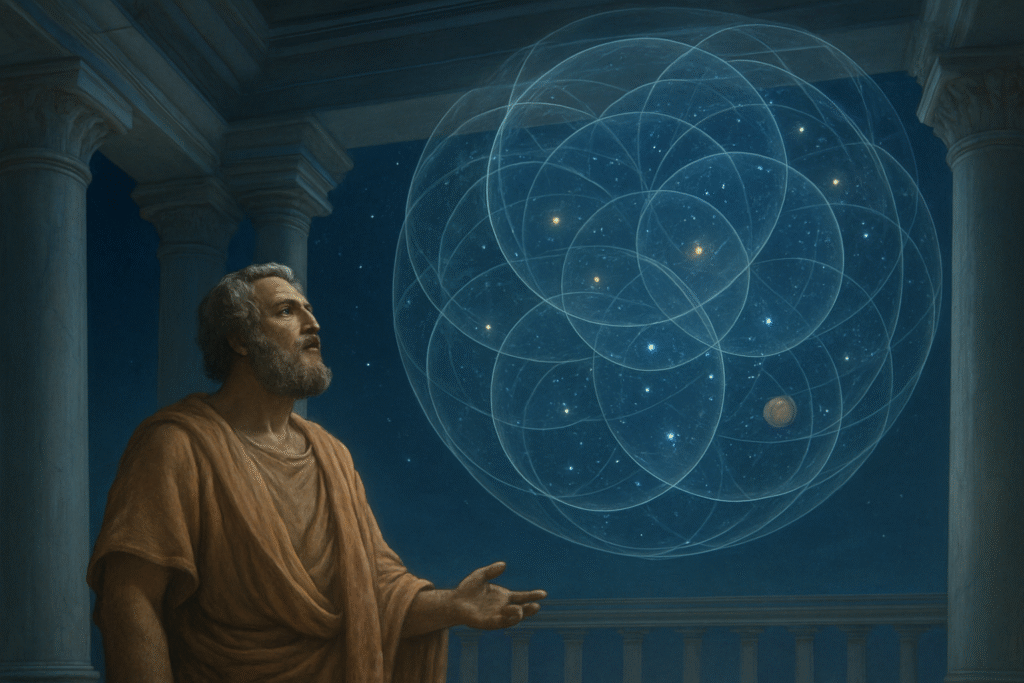

To grasp the courage of Pytheas’s voyage, we have to understand the world he left behind. The 4th century BC Greek cosmos was a masterpiece of intellectual order. Picture it: a series of perfect, nested crystalline spheres, with the Earth at the center. The sun, the moon, the planets, the stars—all were fixed to these spheres, rotating in a silent, divine, and utterly predictable harmony.

“This wasn’t just an astronomical model; it was a philosophical certainty, a beautiful cage for the mind constructed by geniuses like Aristotle.”

It was a complete story. It told you where the world began, where it ended, and where, in the frozen north, life itself was simply impossible. The perfection of the sphere was the bedrock of reality.

What happens, then, when a man sails so far that he finds a crack in that crystal sky?

The “sea lung” that Pytheas witnessed was precisely that—a jagged fracture in the sphere of accepted knowledge. The greatest obstacle he faced was not the ice or the storms, but the flawless beauty of the idea he was about to contradict. He was a man who had seen a new reality, destined to return to a world that had no place for it, a world that would defend its elegant prison of thought with a ferocity that could shatter any single man.

The ancient Greek ship of the explorer Pytheas confronts the mysterious “sea lung” of pancake ice under the midnight sun of Ultima Thule.

The Unraveling of the Human Soul

I can almost hear the whispers that must have spread through the ship, carried on a damp, cold air that smelled of nothing but salt and fear. How long had it been since the crew had seen a true night? The sun, a pale, sleepless eye, circled them endlessly, erasing the sacred rhythm of darkness and dawn that orders a person’s soul.

For sailors from a world of warm, predictable days, this perpetual twilight must have felt like a descent into madness. The stories they told each other to keep the terror at bay—tales of home, of wives and children, of sun-warmed wine—must have begun to sound like fables from a life they would never see again.

“They had already done the impossible. They had circumnavigated the mythical island of Prettania (Britain), a feat that would make them legends.”

But Pytheas, their leader, was not satisfied. He was a man possessed, his gaze fixed on that impossible northern horizon, hunting for something his crew could not see and did not understand.

This is the moment where every great journey of discovery faces its true breaking point. The greatest danger is not the sea, but the crumbling will of the men who have to sail it. I imagine a trusted friend approaching him, his voice low and urgent: “Pytheas, the men are done. Their faith is a frayed rope. We have enough stories to make us kings. Turn the ship for home. Please.”

He was not just their captain; he was the sole anchor for their sanity, and that anchor was dragging them deeper into a beautiful, yet albeit terrifying abyss.

The Weight of an Impossible Truth

The return to Massalia must have been a study in contrasts. Pytheas, gaunt and weathered, stepping off his ship onto sun-warmed stone, his mind still reeling with the silent, spinning twilight of the north. His men, kissing the ground, their joy at being home mixed with the haunted look of those who have seen too much.

How do you begin to tell such a story?

How do you describe the color of a sky that never darkens to men who have only known day and night? How do you explain a sea of breathing ice to people whose biggest fear is a summer squall?

“The disbelief Pytheas faced was not, I think, born of malice. It was born of a profound failure of imagination.”

His discoveries were not just new chapters in an old book; they were a completely different book, written in a language no one else could read. His precise astronomical measurements, his data on the ocean tides and their connection to the moon, his descriptions of the discovery of Thule—these truths were too jagged to fit into the smooth, perfect sphere of their understanding. This reflex, this deep human instinct to protect a comfortable story from a disruptive truth, did not die with the ancient Greek explorers.

It is a pattern that echoes through history.

A visualization of the ancient Greek geocentric model, showing the Earth enclosed by perfect crystalline celestial spheres.

The Geologist Who Saw a Puzzle

Fast forward two millennia. The year is 1912. The greatest minds in geology rest upon a certainty as solid as the ground beneath their feet: the continents are fixed, immovable anchors in the planet’s crust. It is the bedrock of their science.

Then a German meteorologist, an outsider named Alfred Wegener, commits an intellectual heresy. He dares to look at a world map and see not a static picture, but a puzzle. He sees the coastline of South America that seems to ache for the curve of Africa. He sees identical fossils and unique rock formations separated by thousands of miles of churning ocean.

He proposed that the continents were adrift. He called it continental drift.

“The response from the high priests of geology was not polite debate; it was volcanic scorn. His life’s work was branded “utter, damned rot.””

He was dismissed as a deluded amateur, a dreamer whose ideas were a threat to the established order. The comfortable map of the world was more important than the truth.

Wegener would not live to see his vindication. He died on the ice of Greenland, an outcast to the very field he sought to enlighten. It took another fifty years for the discovery of plate tectonics to prove that he was right all along. His impossible truth, like the slow, inexorable drift of the continents themselves, could not be denied forever.

The Lonely Victory of the Truth-Teller

Why is this pattern of scientific discovery and rejection so painfully familiar? Pytheas and Wegener share a common, quiet tragedy. We claim to seek the truth, yet we so often crucify the truth-tellers. We build monuments to our explorers, but only after they have died in the wilderness of our own disbelief.

It is a behavior that seems profoundly connected to every era, culture, and time of human existence. It is a state of our very nature and I fear we have not learned from the past. You can explore more on this topic in our article, “The Ghost in the Glue.”

It was easier for the scholars of antiquity to call Pytheas of Massalia “the greatest of liars” than to accept that their perfect, crystalline sphere of the cosmos was cracked.

“It was easier for the geologists of the 20th century to ridicule Wegener than to admit the very ground they stood on was not as solid as they had believed.”

But here is the beautiful, enduring hope their stories leave us.

Their personal vindication may have come too late, or not at all. Yet their truth survived. The continents continue their silent, unstoppable drift. The tides, even now, answer to the pull of the moon, just as Pytheas recorded. The sphere was shattered, and what rushed in to fill the void was not chaos, but a universe infinitely larger, more complex, and more magnificent than anyone had dared to imagine.

They did not destroy the world; they gave us a bigger one.

Alfred Wegener in his study, contemplating his revolutionary but dismissed theory of continental drift with his puzzle-like map.

This, I believe, is the echo that calls to us across the ages. Each of us is born into a world encircled by our own celestial spheres—the settled dogmas, the unquestionable traditions, the comfortable “truths” that define the edges of our possibility. They are given to us by our culture, our families, and our own fears.

“To stand before them, to see a crack, and to have the courage to follow where it leads, is the hardest journey of all. It can be a lonely path, filled with the sting of ridicule and the pain of being misunderstood.”

But the lesson of Pytheas is a quiet, hopeful whisper that tells us the journey is everything. True victory is not found in the roar of the crowd or the glory of being proven right in our own lifetime. It is the unshakeable, internal triumph of holding true to what we have seen with our own eyes and measured with our own hands. It is the discipline to persevere when the world tells us we are wrong, not for the sake of fame, but for the sake of a truth that is aching to be born.

It is the choice to sail toward our own Thule, to trust our own compass, and in doing so, to discover a world far grander than the one we were told to accept.

Join The Project

The inquiry doesn't end with this article. Our weekly newsletter is where The Project continues. Each week, we deliver new findings—from deconstructing ancient history to forging philosophical thought experiments. It's our expedition into the source code of the human story, delivered directly to your inbox.

We are JD Lemky. He’s a physical chemist trained in academic rigor; she’s an editor with degrees in both literature and biochemistry. We use a scientist’s skepticism and a storyteller’s eye to challenge the official history, exploring the echoes of lost worlds to find what they can teach us about our own.