What if the first step towards the God of the modern world wasn’t taken in a blaze of divine revelation, but in the dusty, torch-lit streets of an ancient Sumerian city? Imagine a man, Abram, standing beneath the colossal Ziggurat of Ur, a man-made mountain dedicated to the moon god Nanna. The air around him is thick with the scent of roasted barley, bitumen, and the murmur of prayers to a whole pantheon of powerful, often capricious, deities—the Anunnaki.

This was his world. This was his heritage. He was a Sumerian, a man of Mesopotamia, and the stories he knew from childhood were not of Eden, but of gods who descended from the heavens to shape humanity from clay and rule over them.

“So when a voice spoke to him, a voice that commanded him to leave his country, his people, and his father’s house for a land unknown, what did he truly hear? Did he understand this as an entirely new God, a being outside of all creation? “

Or did he, perhaps, hear it as the call of one of the Anunnaki, a powerful god choosing him for a special purpose, just as the gods had always chosen mortals in the stories of his ancestors?

This single question is a doorway. If we dare to step through it, we begin a journey not just into the past, but into the very code of our spiritual beliefs. We discover that the lines between Sumerian Mythology and the Bible, between the Anunnaki and the God of Abraham, are far more porous than we might imagine. We are about to trace a kind of spiritual DNA, a sacred code written into the heart of our oldest stories, that have survived for five thousand years.

A River of Stories: What is the Sumerian Influence on Genesis?

To understand Abraham’s context is to understand the cradle of civilization itself. Sumer, in southern Mesopotamia, was a land of breathtaking innovation. They gave us the wheel, writing, and vast legal codes. But their most enduring legacy might be their stories—the very first attempts by humanity to write down their understanding of the cosmos, of their creators, and of their purpose. These weren’t just myths; they were the operating system of their society.

When we place these ancient Sumerian tablets side-by-side with the book of Genesis, the echoes are impossible to ignore. It is not about one text “copying” another, but about a profound and continuous current of human thought. It’s an exercise in Comparative Mythology that reveals not theft, but inheritance.

An artist’s depiction of Abraham standing before the great Ziggurat of Ur in ancient Sumer.

The Creation of Order from Chaos: Sumerian Creation Myths vs. The Book of Genesis

Let’s begin where it all begins. The Sumerian creation myths, which later evolved into the famous Babylonian epic the Enuma Elish, tell of a time of primordial chaos. There was only a formless, watery void. From this void, the gods emerged, and a great cosmic struggle ensued, culminating in the chief god bringing order to the universe by separating the waters above from the waters below and fashioning the heavens and the earth.

Does this sound familiar?

Genesis 1:2 describes the earth as “formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.” The subsequent verses describe a divine being bringing order from this chaos, separating light from darkness, and, crucially, separating the “water under the expanse from the water above it.”

“The Sumerian influence on Genesis is not just in the broad strokes but in the specific details. “

However, the true difference, the revolutionary “mutation” in the spiritual code, lies in the purpose of humanity. In the Sumerian version, the Anunnaki gods create humans for a pragmatic reason: they are tired of doing the manual labor of maintaining creation and want a race of slaves to do it for them. Humanity is an afterthought, a workforce.

Genesis presents a radical re-framing of this archetype. Humanity is still created from the earth (“adam” from “adamah,” earth), but they are not made as slaves. They are made in the image of God and given stewardship, a sacred responsibility to “work it and take care of it.” The narrative structure is inherited, but the philosophical and spiritual meaning is transformed from servitude to partnership.

The Sargon and Moses Connection: A Shared Archetype?

The parallels extend beyond the cosmic and into the deeply personal. One of the most foundational stories in the Sumerian-Akkadian world is the legend of Sargon the Great, who founded the Akkadian Empire around 2300 BCE. His birth story, inscribed on tablets centuries before the biblical narrative of Moses was written down, is startling.

Sargon tells his own tale: “My high priestess mother conceived me, in secret she bore me. She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid. She cast me into the river which rose over me.” He is then rescued by a water-drawer, Akki, who raises him as his own son, and he eventually rises to become king.

Now, let’s journey forward in time more than a thousand years to the story of Moses. A Hebrew mother, desperate to save her infant son from a pharaoh’s decree of death, places him in a basket of papyrus, seals it with tar and pitch, and sets it among the reeds on the bank of the Nile. He is found by Pharaoh’s daughter, raised in the court of the king who sought his death, and rises to become the leader and lawgiver of his people.

“The parallels are too precise to be coincidental. This is the enduring power of archetypes—a core sequence in our shared mythological DNA. “

The ‘hidden child of destiny’ saved from water and obscurity to change the world. The story of Sargon created a powerful mythological template for kingship and divine favor in the ancient Near East. The authors of Exodus appear to have used this well-known, powerful motif to frame the significance of their own hero, Moses, showing that he was a figure of the same epic, history-altering stature as the legendary Sargon.

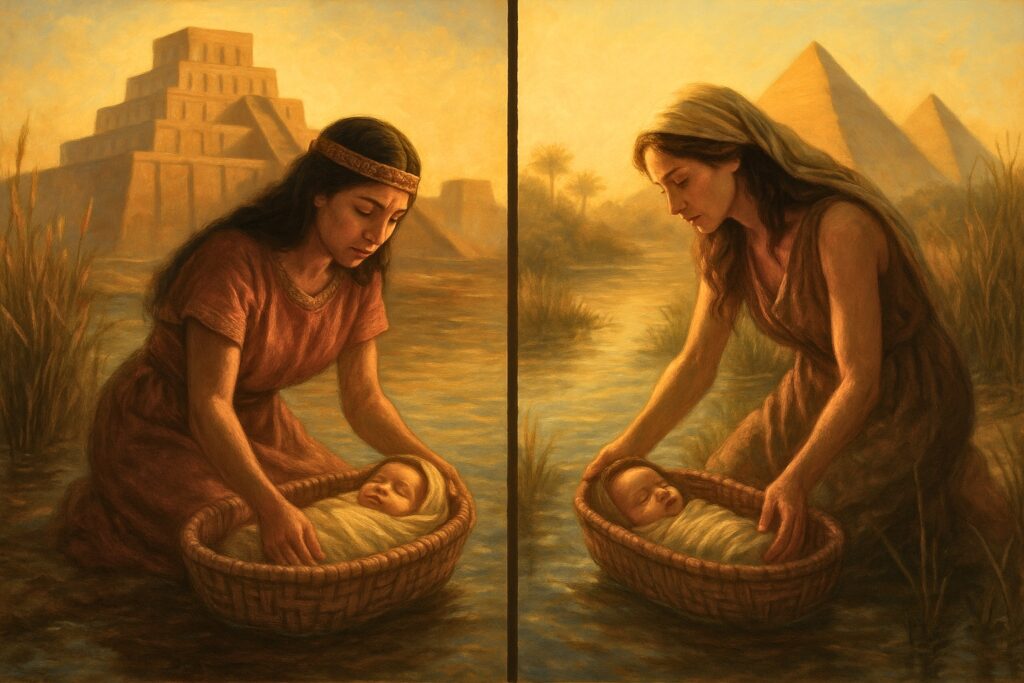

A comparative image showing the similar stories of Sargon of Akkad and Moses being placed in baskets as infants.

The Epic of Gilgamesh vs. Noah’s Ark Flood Story

When the Heavens Wept: The Universal Flood

Perhaps the most famous and compelling connection lies in the story of a world-destroying flood. Long before the story of Noah and his ark was compiled, the Sumerians were telling the tale of Ziusudra. This story was later incorporated into the Epic of Atrahasis and, most famously, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero seeks immortality and meets Utnapishtim, a man who survived a great flood sent by the gods. Utnapishtim’s tale is stunningly similar to Noah’s. The gods, led by the storm god Enlil, decide to destroy humanity because their noise is disturbing their divine rest. But one god, Ea, feels pity and secretly warns Utnapishtim.

- A Secret Warning: Ea speaks to Utnapishtim through the reed wall of his hut, telling him to tear down his house and build a boat.

- Specific Dimensions: Utnapishtim is given precise instructions for the boat’s construction.

- Saving Life: He is told to load the “seed of all living things” into the boat, along with his family and craftsmen.

- The Deluge: A terrible storm rages for six days and seven nights, covering the earth with water.

- A Mountaintop Landing: The boat comes to rest on a mountaintop.

- The Birds: Utnapishtim sends out a dove, then a swallow, then a raven to see if the waters have receded. The raven does not return.

- The Sacrifice: Upon leaving the boat, Utnapishtim offers a sacrifice, and the gods, smelling the sweet savor, gather around.

The story of Noah in Genesis follows this narrative beat for beat. From the divine command and boat construction to the saving of the animals, the landing on a mountain, the sending out of the birds (a raven and three doves), and the pleasing sacrifice afterward.

“The timeline is undeniable: the surviving tablets of the Epic of Gilgamesh Noah’s Ark predecessor date back to at least 1800 BCE, nearly a thousand years before the Genesis account was likely written.”

This doesn’t invalidate the story of Noah. It enriches it. It suggests that the memory of a catastrophic flood was so deeply seared into the cultural memory that it became the ultimate story of divine judgment and divine salvation. A story retold and reinterpreted by generations, each weaving their own philosophical and spiritual understanding into its ancient frame.

From Anunnaki to Abraham: A New Idea of God

From the Many to the One

Let’s return to Abraham, standing in Ur. His mind was filled with these stories—of creation by committee, of abandoned kings, of a flood sent by angry gods. The Anunnaki gods were real to him, as real as the sun and the moon they represented. They were powerful but also flawed, exhibiting jealousy, anger, and impulsiveness. They were, in many ways, super-powered, immortal humans.

So, when this new call came, how did the Abraham Sumerian connection shape his understanding? Perhaps the journey from the polytheism of the Anunnaki to the monotheism we know today was not a sudden leap but a slow, profound evolution of thought. Could it be that Abraham, and his early descendants, were not pure monotheists but henotheists? That is, they worshipped one chosen god above all others while still acknowledging the existence of the others.

The Bible itself contains echoes of this. The first commandment is “You shall have no other gods before me.” This is not a statement that other gods do not exist, but a command for exclusive loyalty. The term for God, ‘Elohim,’ is a plural word in Hebrew. While it’s used with singular verbs to denote a singular God, its etymology is plural. It points to a time when the concept of the divine was more fluid.

“From this perspective, the God of Abraham can be seen as a radical reinterpretation of the Anunnaki archetype. “

This was not just another tribal god jostling for position. This was a god that transcended the squabbles and flaws, a god who represented not just power, but justice, covenant, and a universal moral law. The ancient spiritual DNA was being intentionally re-sequenced, transforming the raw materials of ancient religions into something entirely new.

The Unbroken Thread: Our Shared Spiritual DNA

To walk this path of comparative mythology is not to tear down the walls of faith, but to see the ancient bricks from which they were built. It connects us to a human story that is far older and more universal than we knew. The questions the Sumerians carved into clay tablets are the very questions we whisper to ourselves in the quiet of the night: Where did we come from? Why are we here? What is our relationship to the power that animates the universe?

The stories of creation, of floods, and of chosen saviors are not just Hebrew or Sumerian. They are human. They are the software our ancestors wrote to make sense of the world.

“Perhaps Abraham’s great revelation was not the discovery of a new God, but the discovery of a new idea of God—an idea that took the most powerful stories of his people and infused them with a new, profound, and loving purpose.”

And so, the voice that spoke in the Ziggurat’s shadow still echoes today. It is a voice that has traveled through millennia, been translated across languages, and been filtered through countless cultures. It’s the code of our spiritual DNA, reminding us that our search for the divine is the most ancient and unbroken thread in the epic story of humanity.

Join The Project

The inquiry doesn't end with this article. Our weekly newsletter is where The Project continues. Each week, we deliver new findings—from deconstructing ancient history to forging philosophical thought experiments. It's our expedition into the source code of the human story, delivered directly to your inbox.

We are JD Lemky. He’s a physical chemist trained in academic rigor; she’s an editor with degrees in both literature and biochemistry. We use a scientist’s skepticism and a storyteller’s eye to challenge the official history, exploring the echoes of lost worlds to find what they can teach us about our own.